Hello, fellow lovers of all things green. The history and impact of Hyper-Humus Inc.’s peat mining are fascinating and disturbing. Gratefully, a restoration project is underway to help heal the harmful effects of peat harvesting on wildlife and our environment. And there are things we can do in our communities and gardens to support the cause.

Our Winter Wonders Group

The Winter Wonders of Hyper-Humus Walk

I recently enjoyed a walk with a group of folks and learned the history and impact of Hyper-Humus Peat Mining. The Paulins Kill Rivershed Watchers hosted the event with their parent organization, the Food Shed Alliance — a nonprofit helping farmers, feeding people, and protecting the environment. Hyper-Humus is a company that once harvested peat moss, changing the lay of the land along the Paulins Kill River.

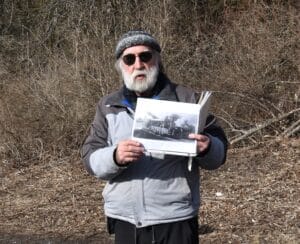

Chris Dunbar and David de Wit

What a delight to meet Chris Dunbar, the Paulins Kill Watershed Coordinator, and event organizer, along with David de Wit, a local naturalist who led the discussion during the four-mile hike around the Paulins Kill and the former site of the Hyper-Humus plant. The history is fascinating and disturbing at the same time. As you may know, using peat moss in the horticultural industry and as a source of fuel has lost favor in a big way.

David’s dynamic and colorful delivery was captivating. (I invite you to tune into the podcast Episode 195 below.)

History of the Hymer-Humus Section of the Paulins Kill Rivershed

“The Meadows and the town of Newton were surveyed in 1715, but nobody showed up to buy a piece of land until around 1750, and the guys that showed up didn’t bother buying it from William Penn’s son, who wasn’t very nice. They just squatted and started farming, doing what they did to survive here throughout the 1800s. Occasionally, people had to go with ropes and drag their cows out of the muck because it was not a solid meadow. If parts were impassable, they cut the timber off it, mostly red maple, which they didn’t want,” David said.

Red Maple doesn’t burn well and is not sound for furniture because it twists and turns when it dries.

“Around 1900, they discovered a market for peat, and farmers would come to get some in a wagon, take it up to their farm, and spread it on their gardens. It was great fertilizer.”

David described peat as mostly rotted vegetation. “There are two kinds of peat: sphagnum peat and sedge peat. Sedge Peats are grasses, canes, and forest leaf litter that get deposited year after year.”

Peat can regenerate 1/32nd of an inch annually, but it takes thousands of years to form a significant layer. Plus, the carbon and methane gases the peatlands hold safely below are released into the atmosphere when dug up. Carbon dioxide is believed to contribute significantly to climate change. Then, there’s the impact on wildlife by destroying habitat.

Hyper-Humus Inc. straightened a section of the Paulins Kill River.

The first water-powered mills were built in the 1770s, and the first effort to channel and drain the Hyper-Humus area began in 1806. In 1836, the New Jersey General Assembly passed an act, ‘Drain the Swamp.’ Then, in the 1870s, fires, floods, and drought impaired the active use of the meadows. Hyper-Humus Incorporated began in 1915, followed by more draining of the Paulins Kill Meadows.

The Harvsting Process of Hyper-Humus Peat Mining

David worked for Hyper-Humus during a summer break from teaching and described the harvesting process.

Dave de Wit Explains Hyper-Humus Peat Mining

” Once we’d taken all the trees and stumps off, they’d bring a bulldozer in on great big, wide tracks and bulldoze all the living plant material and debris up in the pile. And then we’d send in the guys with the bulldozers to scrape up wind rows of peat. A device that looked like a combine with a chute would go over the wind row once it was dry enough, and you’d fill up the Bombardier trucks. And these are trucks with huge, wide tires on wooden tracks. Why? Because, if you spread the weight out enough, nothing will sink in this muck–you hope. Later, they switched the trucks to get this stuff out of here.”

Where did Hyper-Humus peat go?

“Rumor has it the White House lawn is made with Hyper-Humus peat. Every golf course on the East Coast supposedly has hyper-humus peat mixed in with it. It is the world’s best soil additive if you want good, rich soil that holds moisture and provides some fertility,” David said.

When he worked there, I asked if he felt the peat mining insulted the earth.

“I did and then heard their rationale that we are creating habitat for migratory birds. And truthfully, they were. It’s gone through iterations. When I worked here, there was a whole line of enormous red maple trees, a few which survived along the western side of the stream, and big blue herons nested there. And there was a heron rookery. There were about 10 of them that summer I worked here in their big stick nests. They’d always be fishing for frogs and whatever else.”

Hyper-Humus Area of the Paulinskill River Wildlife Management Area

From 1985 to 1988, ownership changed. Hyper-Humus was bought by Hyponex and then by Scotts. In 1990, provisions of the Clean Water Act halted the strip mining of the peat, and in 2005, the State of New Jersey purchased the area as a Wildlife Management Area.

Plans to Heal the Effects of Hyper-Humus Peat Mining

Ed Samanns, with WSP, a consulting company, worked with the Nature Conservancy and New Jersey Fish and Wildlife, which manages the property, to develop a restoration plan for the Paulins Kill River and the adjoining forest and marsh systems “to bring it back from the changes that occurred over the years so that it acts as a more natural system.”

A Bald Eagle captured our attention. Ed Samanns, with WSP, on the left.

Hyper-Humus widened and straightened the channel so water would drain more quickly. The restoration plan calls for adding back the channel’s sinuosity, the natural twists and turns, to improve the water quality.

They looked at Whittingham, another wildlife management area with a similar peat meadow system with minimal alteration. “You’ll see a nice, sinuous channel that hasn’t been altered for a long time, thousands of years. So, that became a reference for a natural channel design. It isn’t straight like this.”

“We took measurements to determine the sinuosity – how many bends per thousand feet the channel should be. We also looked at the highly sinuous East Branch of the Paulins Kill,” Ed said.

The Science Behind the Proposed Hyper-Humus Restoration Plans

Michelle DiBlasio, Nature Conservancy’s Freshwater Restoration Manager, said, “Of all the sites across the watershed, year after year, we see the poorest water quality coming out of this one-mile stretch of river.”

Michelle DiBlasio, Nature Conservancy’s Freshwater Restoration Manager

She shared how they measure water quality based on water temperatures and dissolved oxygen. In summers, the area often runs from 28 to 30 degrees Celsius, well over the 25-degree Celsius average needed to maintain the trout populations throughout the year. And the oxygen levels are usually below 4.

“Critters in our streams need at least 6 milligrams per liter of dissolved oxygen. Ideally, they want 7 to 8 milligrams. The restoration project will entail about 1000 acres, with about a mile of stream. That’s pretty significant. It’s hard to make big changes to water, but something like this could truly impact the water’s quality,” Michelle said.

After they receive permits, likely at the end of March, the next step is to secure funding to do the work in three phases, which will take years and millions of dollars.

Support the Effort by using Peat Moss Alternatives.

Leaf Mold makes an ideal soil supplement and mulch.

We can support the cause by using alternatives to peat moss, such as compost, composted manure, locally sourced bark, and sawdust for plants that prefer acidic soils. Be sure not to use chemically treated wood byproducts, which sadly comprise most dyed mulches folks like to use – a pet peeve of mine.

There are pine needles and Vermiculite, a hydrated magnesium-aluminum-iron silicate. It’s non-toxic, has a neutral pH, and improves heavy or wet soil. And let’s not forget my tried-and-true leaf mold. By the way, many potting mixes include peat moss, so look for those that don’t.

You can also support the effort by donating or volunteering for restoration projects in your area. Every effort multiplies to help make a big difference.

An analogy of restoration in our lives

Undoubtedly, things won’t be restored as they were in the 1700s. Much like when we go through hardships, we carry wounds (I call stretch marks) from the history of our past. But they fade as we move forward and new growth begins. The scars are badges of wisdom gained. We’ll still call the area the Hyper-Humus section of the Paulins Kill River Wildlife Management Area. By keeping the name of the “stretch marks,” we will remember and learn from what happened there. May the lesson never fade.

Garden Dilemmas? AskMaryStone@gmail.com and your favorite Podcast App.

There’s more to the story in the Garden Dilemmas Podcast (@15 soothing minutes):

Related Posts and Podcasts you’ll enjoy:

Preservation of the Paulins Kill River – Blog Post

Ep 185. Preservation of the Paulins Kill – Overcoming Hardships

Leaf Mold—Better than Mulch – Blog Post

More about the Paulins Kill Watershed River Watchers and the Food Shed Alliance.