Hello, fellow lover of all things green, During winter walks through the woods, the bark of trees takes center stage, especially standing in the snow. I confess to not being the best and identifying species without leaves unless a few are on the tree or the ground nearby. Bruce Crawford gave a talk on Bark Basics at the NJ Nursery & Landscape Association event that turned out to be a fascinating lesson on the array and anatomy of beautiful bark, along with an assortment of trees he admires.

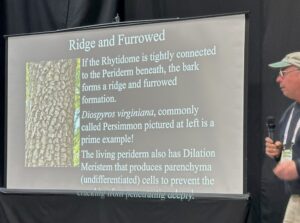

Ridge and Furrowed Persimmon Bark

The Anatomy of Bark Works Much Like Our Skin

Bark works like our skin, keeping innards intact and protected. It helps maintain water and expands as we grow or exfoliate, making room for new skin.

A Majestic Oak with Plately Bark

Metaphorically, we grow thicker skin as we age. We toughen up after life challenges us. Thankfully, we can forgive and let go. Stretch marks can occur during pregnancy and episodes of weight gain and loss or rapid growth, which happened to me at age 16. I grew six inches in less than a year, gratefully stretch marks can fade. The same applies to trees.

‘Medullary Rays,’ also known as pith rays or tiger stripes, are the white marks sometimes curved, especially prominent on fine oak furniture, “adding charm, character, and overall beauty to any oak furniture piece,” writes PictureWood.com. Have you noticed what looks like skin folds at the base of branches? Outcomes of growth in the stretch marks can be attractive. It’s a matter of how you look at things.

Some trees, like Beech, shed their skin quickly while others, like Pine, do so slowly, causing the outer layer of their skin, their bark, to grow thick and crack. But the inner layer of the bark is smooth, fitting the trunk’s width. But American Beech bark begins to wrinkle too, starting from the bottom when it reaches middle age, say 150 or 200 years old. The older the Beech Tree, the deeper the cracks. Sound familiar (smile)?

Native Americans called Sycamore Trees Ghosts of the Forest

An Array of Beautiful Bark

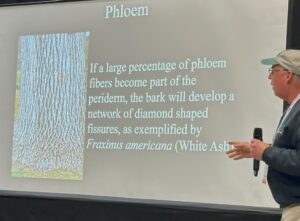

Each tree species has developed a unique bark that evolved over millions of years. There’s Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana), which has alligator-like bark. It’s native to the southeastern United States. White Ash, Fraxinus americana, has lovely diamond-shaped patterns in the bark. Sadly, emerald ash borer is devastating the Ash Trees.

Some trees have bark that photosynthesizes like Aspen Trees. River Birch and Paper Birch photosynthesize through their Exfoliating Bark, even on warm late winter days, giving them a jumpstart to other deciduous trees, hence why they grow so quickly.

Cherry Bark with prominent lenticels

Birch trees, like Cherry Trees and Tree Lilacs, also have prominent lenticels. Lenticels work much like tiny windows, allowing trees to breathe. All plants have them, and they are on fruit surfaces as well. They look like dots or narrow etched lines.

The stunning Exfoliating Bark of Paperbark Maple (Acer griseum) and Three-flowered Maple (Acer triflorum) are other beauties to add to your garden.

There’s the Patchy Bark of Kousa Dogwood (Cornus Kousa) and American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) as well as Stewartia (Stewartia monadelpha is more orange than S. koreana.)

Bark developed to adapt to the environments of origin.

Shagbark Hickory has Plately Bark as does Kentucky Coffee Tree (Gymnocladus dioicus). And because Kentucky Coffee Tree leaves are so large, the wood structure in winter is especially dramatic because it doesn’t have small twigs. “You will love it without the leaves. And if you don’t like the pods, grow a male tree,” Bruce said.

Shagbark Hickory’s Plately Bark

Our beloved Northern White Oak (Quercus alba) also has Plately Bark, and it’s a gorgeous native tree that supports many forms of wildlife.

Seven-Sons Flower with Unique Peeling Bark

Then there are trees with Peeling Bark, some with long strips, such as Seven-son Flower (Heptacodium) and Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana.) Bald Cypress (Taxodium ascendens) is an underused tree with lovely peeling bark that does well in wet and dry conditions and tolerates salt.

Some Smooth Bark trees are the Japanese Maple (Acer palmatum) and American Hornbeam. Another underused native tree is Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis) with striking pebbled bark.

Ginkgo biloba has Ridge and Furrowed bark, as does Sourwood(Oxydendrum arboretum), which blooms in July and is native to the eastern and southern United States. Then there’s Colorful Bark, such as Red Maple (Acer rubrum.) Its stems or redder in the winter. Red Twig Dogwood (Cornus sericea) has greener stems in the summer.

It’s fascinating how trees have adapted through millions of years.

White Ash Bark has Diamond-Shaped Fissures.

In recent years, we all know the sad demise of the ash trees from the emerald ash borer and Beech leaf disease is spreading. We wonder why these things are happening. Perhaps Mother Nature’s way of checks and balances.

When trees die and fall, sprouts of new branches from surrounding trees emerge from the dormant latent buds tucked in their trunks that wake up with the increasing light. Just as when we shed the wounds from our past, by forgiving, we begin to flourish.

Garden Dilemmas. AskMaryStone@gmail.com and your favorite Podcast App.

There’s more to the story in the Garden Dilemmas Podcast (@10 soothing minutes):

Bruce Crawford, Manager of Horticulture of the Morris County Park Commission (NJ

The Cliff Notes of the Anatomy of Bark

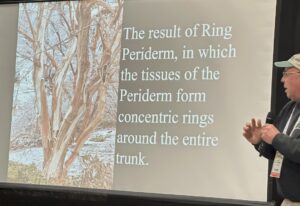

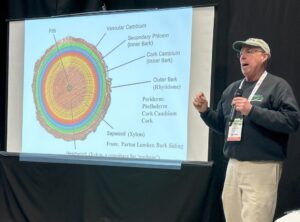

Bruce shared slides of the anatomy of trunks and bark and gave an impressive explanation of the function of each part. A cliff-notes version: The trunks of trees are primarily dead tissue to support the tree or shrub. Only the outside layers of trunks are living. The Outer Bark (Rhytidome) protects the tree from the elements, insect invasions, and from losing moisture and constantly renews from within.

The Inner Bark (Phloem) is the food pipeline of the tree and lives for a brief time before turning into cork, part of the protective outer bark.

Then there’s the growing part of the trunk, called the cambium cell layer, that produces new bark and new wood each year triggered by the hormones (Auxins) transported through the Phloem from the leaves. Pretty cool! I hope you find it so, too.

Water moves through the new wood, called Sapwood, to the leaves. As new rings form, the old rings become Heartwood, supporting the tree. Though Heartwood is not alive, it does not deteriorate or lose strength as long as the outer layers of bark are primarily undamaged.

A tree will most likely recover if less than twenty-five percent is injured. Remove any detached bark, leaving the healthy bark and allowing the tree to heal—no need for tree paint or sealers.

Related Stories and Helpful Links:

Beloved Beech Trees featured in Episode 45, Beloved Mr. Beech

Shagbark Hickories – Nutty Mast Years featured in Episode 132

Another beautiful column/podcast. Educational and fascinating. I will never again look at a tree in quite the same way. Thank you Mary.

You are so kind, Ken! I find myself marveling at all the textures, how bark wounds have healed, and the miracle of it all. I appreciate your support; it means so much, Mary